Inner Ear Recording

Arlington, VA

Hear from Don Zientara's Students

Notable Clients of Don Zientara

-

The Foo Fighters

-

Fugazi

-

White Zombie

-

Jimmy Eat World

-

Special K

-

Bad Brains

-

Minor Threat

-

Bikini Kill

-

Group Love

-

Against Me

-

OAR

AMPLIFY YOUR LIFE

WITH AUDIO

ENGINEERING AND

MUSIC PRODUCTION

IN-PERSON MENTORSHIP

Are you our next Success Story?

"*" indicates required fields

Notable Apprentices:

Meet Your Music Pro, Don Zientara

Q. On Punk

Recording Connection mentor Don Zientara on Punk, Recording Mimes, and Music Business

Get two engineer/musicians on the phone talking about music and gear and you can get quite a conversation going. With more than three decades in the business, record producer, audio engineer and musician Don Zientara is a downright legend in the punk music scene (just see his Wikipedia page).

He’s worked with basically everyone who was blazing the trail in punk back in the early 80s (Minor Threat, Fugazi, Bad Brains) and he hasn’t stopped since.

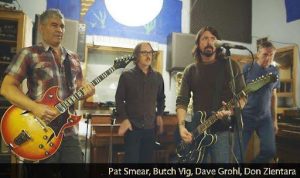

So, it wasn’t surprising to see that our interviewer, a touring musician and audio engineer who will remain nameless for now, had a fantastic time hearing what Don had to say about punk, recording, and his somewhat circuitous path into the business. We touched base with Don just shortly after he’d had Dave Grohl, Butch Vig and the Foo Fighters in to record at his Inner Ear Recording, located in Arlington, Virginia, just outside of D.C.

ON DAVE GROHL

Zientara: He can play many instruments. You know, there’re just a lot of sensibilities that he has for both the studio and music. Just hanging around and playing with people. By giving of yourself unto other people’s projects, you find out things. And [Dave] did that. He just sort of absorbed it. He absorbed habits and he absorbed different little tricks of the trade. And all these things are just very, very important. And it shows, too. You know, when he’s here, I learn things. And when the group was here, I learned things. They just have – I don’t know, they’re good in that way. But you know, for that matter, most professional musicians are that way. They are very quick learners and they’re sponges for any kind of skill or new skill or thing that comes along that will help them in their craft. Like any professional. You know, if I was a plumber, I’d want to know of a new kind of plumbing supplies or whatever. So it’s that way.

THE LONG, LONG STORY OF HOW DON GOT INTO MUSIC AND RECORDING

Zientara: Basically, back in elementary school I had friends that were involved in electronics and putting stuff together, wiring circuitry, you know, getting huge electrical shocks and things like that. And they were basically just really, really smart. There were a couple of guys that stand out. They were very smart. We hung out together. This is a little community in upstate New York. And we basically knew each other and they helped me out when my mother had the idea that I had to learn an instrument because it’d be sort of good for my musical discipline or whatever. So I had a choice between either accordion or guitar at the time.

This is a Polish community, so the accordion of course was a very versatile instrument. But at the time, Elvis Presley was up on the rise and I thought, ‘Yeah man, this is cool. I’m gonna do the guitar.’ So I got the guitar and I started playing it and I laid it down after a couple of years and stopped taking lessons and things like that. But then I picked it up again just by happenstance and started getting into it and started getting into electric guitars. You know, in a small way. You know, Kent guitars and things like, anything you could buy for less than 30 bucks, I might’ve bought. And I did not have an amplifier. I had a tape recorder, though. I always liked tape recorders. I’ve always enjoyed them. But so I got some of these friends to help me and show me how to wire up a tape recorder to use it so I could plug my guitar into it and play through it. From there came on… of course, I got into the guts of tape recorders and things like that and then the guts of amplifiers. And we would scour trash day and try to find old Magnavoxes and, you know, if they had any usable amplifiers or, hey a cabinet, maybe we could use this for a speaker cabinet or something like that if there were usable speakers in there. So I sort of got into that world where you’re sort of into scavenger electronics. And all this time I really enjoyed tape recorders, just messing around with them at the time. Of course, this was in the ’50 and early ’60s so they weren’t too advanced in that state. And then just hopping a little bit I started playing in groups and bands and musical groups all through high school and through part of college, too. But in college I got into art… And I enjoyed it quite a bit. I got into the visual arts and it really was very, very satisfying. All this time, I was keeping tabs on music, playing music, playing guitar and recording. Recording myself, recording my friends in a very, you know, rudimentary, very, very basic way.

There was a lottery draft back in the late ’60s, where instead of the draft, they figured a more equitable way to do it would be to put all the 365 days of the year into a big spool of barrel and pick one out and pick them out as they go along. And the first one would be the first in line for a draft, and the second one would be the second in line. But I got number one.

RRFC: Oh, wow.

Zientara: So I was going to the army. And I figured this is a perfect opportunity to learn some electronics. So at the time they had a guaranteed program, where if you signed up you could pick your school you went into. And I picked an electronics training school. And obviously you’d work in electronic training or radios and things like that after that. So I went through all basic and stuff like that and waiting for the school and waiting some more and waiting some more. Eventually got called into the headquarters there and they said, ‘Look, we know you’ve got this guarantee for electronics training, but right at this moment there’re a lot of people who are entering into that school. And we’re gonna honor your guarantee, you may have to wait a little while, but if you want there just happens to be an opening for an artist in Washington, D.C.’ And so I said, ‘Well, okay, I’m game.’ You know, I knew painting and I knew how to draw and stuff like that. So I came down here and that was it. I spent all my time in my army here in Washington, D.C.

But the way it worked out, I was here and after I got out of the army, I was [working] at the National Gallery of Art and on one of the occasions, I can’t remember exactly when there was a tour through one of the recording studios they were building for the guides. And they had a problem with wiring, how to get a certain power supply in. And I say, ‘Well, here’s what you do, you have to just wire it up like this.’ And they said, ‘You know how to do this stuff?’ And I said, ‘Well, yeah.’ And they said, ‘Well, why don’t you become the engineer here?’ So I just sort of flipped from the artistic side. I became the audio engineer for the National Gallery.

RRFC: Wow.

Zientara: And then from that point on, I just stayed with audio and stayed with tape recording. And I just recorded everything I could possibly get my hands on. I recorded people basically for the cost of the tape that I put on my recorder. And just did a lot of it. And then, here we are. You know, what? Thirty five years later, 35-40 years later.

RRFC: Well, I like how you glossed over all the amazing albums that you put together and just said, ‘Here we are now.’

HOW PUNK FOUND DON

Zientara: If you hang around long enough you do some stuff. And that’s what was done. I mean, you know at the time we just fall into things. I guess one of the things that I learned from a lot of the people I was around was to grab every opportunity. And I just would say, ‘I’ll record you. You wanna record? Man, I’ll record you. I don’t care if you are death metal. I don’t care if you are folk rock. I don’t care if you are hair metal, pop rock, metal metal, anything. I will record you. And I’ll learn. And you know, I’m just gonna sort of build up this resume or whatever you call it.’ And I did that with both the punk music that was here and I did it with every other music that I could possibly be in contact with. I happened to be in contact with through a number of serendipity-type of things. There are some strange connections that were just connected up. But that basically got me into it.

And as far as just like connecting with the punks themselves, I had a friend from a band that was in, that knew I had a tape recorder and we’re talking about a stereo tape recorder. And he got into another band after our band broke up and he said, ‘Hey, we’re playing at this place, can you record us?’ And so I brought my tape recorder down and there and schlepped the mics and everything and recorded them. But at the time, there was a kind of punk or alternative band that was playing at the same bill as them. And they say, ‘Can you record us at the same time?’ And I said, ‘Well, sure.’ So I did that. And they happened to be connected with one of the mainstays, Skip Groth, of the punk scene in D.C. at the time, who ran a record store here. And he sent a lot of punk groups here. He introduced me to a lot of people who were in the punk scene. Remember, these were sort of musical outcasts at the time and no one would go to their shows. No one would want to book a show with the punks. I mean, they destroy things, they break things up, there’s fights and all kinds of other stuff. There’s blood all over the floor. And, as a matter of fact, when the Bad Brains were first here recording, Skip, you know, said, ‘Hey, why don’t you record these guys?’ And me, I don’t want to touch them. You know, they scare me. So I said, ‘Well hey, I’ll record them.’ You know, just anybody. I’ll record them. Like I said, I’ll record the thing.

And I guess just putting yourself in that situation brings you in contact with just a lot of different forms of music and a lot of different people. And it was enjoyable. It was totally, totally enjoyable. I learned a lot, I just enjoyed a lot. The fact that, you know, you mentioned some of the albums I recorded. I think that some of them were probably not recorded in the best way possible, but you know I did what we could with the equipment we had.

ON RECORDING OTHER STUFF

RRFC: Well, what’s like the favorite thing that you recorded that people may not expect?

Zientara: Probably choral music.

RRFC: Choral music?

Zientara: I enjoy it quite a bit, yeah. Yeah, I enjoy the harmonies and the interweaving of the voices. I don’t do much of it, but when I do I find that I could bring some of that back when I… well, just next week, we start on the project Monday. A pop band. And some of the pop harmonies are… you know, you could really use that technique, the way the voices weave each other into the song and the melody. That, I guess recording, people say, ‘You recorded a mime?! What do you mean? They don’t say anything!’ Well, you know, they need something to back up their act. And it’s almost like background music, but at the same time, for a mime it’s even more crucial because there’s nothing else going on other than the visual.

RRFC: Right.

Zientara: Just anything. Wacky things. Just every possible thing you could think of, you know. I’ve recorded narrations, slide shows, everything. Everything you could think of.

ON GEAR

RRFC: What kind of gear do you just really love in your studio, that you’re really geeked out on?

Zientara: Well, you know I like, constantly, I’m trying new things, I’m keeping some of the old things. Sometimes I purge some things, so there is a little bit of a churning. Not much, but a little bit of a churning here and there.

But my approach to recording… I remember reading, way back in the ’60s, there was basically, you know, someone who knew studios and was a producer at the time, he was asked ‘What’s the most important thing about the studio or setting up to record?’ And he said, ‘Well, there’re a couple. First, you have to get a good monitoring system. Before anything else, before any of the microphones or the preamps or the mixers or anything, you have to get a good monitoring system. Because that’s gonna tell you everything you need to know about what you’re doing. And once you’ve got that, then you could start down the line. And you have to…’ Well, remember this is the ’60s at the time. ‘Then what you do, is you have to dampen your space that they’re gonna record in as much as possible. And then after that you have to get the best reverb unit you can in order to give it some space.’

So, you know, it was kind of timely advice. But his first advice about the monitoring system was really important so I kind of enjoy having a really good monitoring system. It’s not the best that money could buy because I have heard some that are much, much more expensive, but I think it’s very revealing and it’s multi-faceted. In my control room, I’ve got four sets of speakers that I constantly listen to.

RRFC: You ABCD back and forth?

Zientara: Absolutely. Absolutely. Because every band that comes in, if they don’t know it already, I’ll tell them that. You know, you take out any mix and it’ll sound differently in a different room in a different stereo system. So it’s all gonna be different. So what we want to do is, we want to hit the middle ground somewhere. We wanna get what normal is because we don’t know what normal is. All we could do is sort of guess at it by trying different things. So you get some good systems and they’re all gonna be different even though they’re all good. They’re all very good.

RRFC: Right.

Zientara: And I’ve got some Westlake monitors that I like. They’re large monitor systems. I’ve got some Mackie 824s active monitors that I enjoy. And I’ve got NS10s. And I’ve got another Infinity system that is more home-based, but it still reveals a lot of things that the other systems don’t. And I think that’s very important. Having the right power amps. Having power amps that can really deliver what you need to the speakers is important. Having the mixing console there with some good preamps is important. I have the Amek Angela that isn’t made anymore, but I really enjoy the preamps that they have in there. I enjoy the routing that they have. The routing is extremely flexible. And if you think of the mixer as sort of the heart and the control central for the whole studio, the mixer has to be able to route things to different places anywhere you want. And this does it.

RRFC: Does it allow you to like switch to the [inaudible 00:38:57] from pre to post and all that?

Zientara: Anything, yeah.

RRFC: Great.

Zientara: Really anything. You know you really are unlimited in a sense. And once you can knock that up to a good computer-based system, like Pro Tools, it has completely limitless possibilities. I record both to tape, I have a 24-track two inch recorder and then I record to computer too. And as a matter of fact, the last system we did, the last band we did, we recorded the drums and base and a first guitar to tape and then we bounced it to the computer. And I think a lot of studios are doing that these days because they can see that tape has certain advantages and computers have certain advantages. And why not use what is best for both?

I mean, if I was a carpenter and I needed to screw in a Phillips head screw, I wouldn’t get a flathead screwdriver to do it. I would use the correct tool. And that’s exactly what’s happening here.

I enjoy good preamps, whatever good preamps are. I like colored preamps, something with a little bit of character to them. But different preamps are different colors, I really enjoy getting into that. I enjoy compressors a whole lot. I have a whole… I think I’ve got about 25 different compressors in the studio.

RRFC: Really?

Zientara: Each one doing a little bit different job on compression. And I enjoy matching that up with a voice here or a guitar there or a drum mix here or there. And, as a matter of fact, I’m just about ready to build a compressor with one of my students.

RRFC: Really?

Zientara: And I’ve built, let’s see, three compressors in the past. You know, from scratch, that is.

RRFC: Do you use the DIY kits you can get online?

Zientara: I’ve done the kits and I am gonna do a kit, but I’ve done the regular ones from scratch, where you basically get just a circuit board and wire it up by hand. That way you can get to intimately know how the circuit runs. And you can say to yourself, ‘Okay, well, this is the way it goes but what if I want to do this? How would I affect that?’ And you sort of look into it and I’m looking at this right now, you know, it’s called an active filter cookbook. And it’s got all sorts of schematics that you could use to alter the different components in there. It’s just fascinating, it really is fascinating.

RRFC: Great.

Zientara: So, and then, of course, to top it all off I get to experiment on musicians.

RRFC: Right.

Zientara: So, it’s the best of both worlds.

RRFC: You’re making your own secret weapons at this point.

Zientara: Yeah. Yeah, exactly.

RRFC: That’s pretty cool. That’s pretty cool.

Zientara: And actually, the early punk recordings were done with a mixing board that I built myself.

RRFC: Really?

Zientara: Yeah. Well, at the time, remember, the ’70s did not have a proliferation of Behringer and Alesis mixers and Mackie and all that stuff.

RRFC: Or Midas. Yeah.

Zientara: Yeah, Midas. I mean that was really high end gear at the time. But you would have them if you wanted them in a professional studio, in which case they were large and expensive. Or if you wanted them on the road, which also were large and expensive, too. But if you wanted to record, say, and you wanted 8 inputs or 10 inputs and 4 outputs. You could find nothing. So you had to build them yourself. And I did that. And luckily in this era, it was still going on through the ham-radio era, where people were building their own ham radios and, you know, going into short wave and things like that. So, building electronics and things like that was not that weird of a thing to do. People would do that. And I was just another one, but I was building for the recording side of things.

RRFC: Right.

Zientara: And so I had that going for me. And I’ve still got the mixer in my attic right now. It’s been superseded many times by many other mixers, but, you know, it was a good mixer. It served the purpose at the time.

RRFC: And is it funny to watch, you know, guys ripping apart these old mixers today and making like these lunch box units out of like something that maybe you were already doing, you know, 30 years ago?

Zientara: No, I kind of enjoy it. I enjoy all kind of, you know, innovations and you know if they could repurpose a mixer that, you know, nobody really… or demand for the entire mixer’s not that much, but the demand for single units of the mixer may be far more, why not? Why not?

RRFC: Yeah.

Zientara: Yeah, but it all works. They’re using it and that’s their thing and if someone wants to buy it and use it, fine, do. I mean, I think that you could buy a big mixer for a song and a dance these days. Why not make them into 500-style units and probably get 10 times more for the actual parts?

RRFC: Yeah, I guess that’s true. Yeah, a buddy of mine, he just bought a 500-series version, but it’s like from an old MCI board. And I was like, ‘Wow, that’s going back a ways.’

Zientara: Yeah.

RRFC: Yeah.

Zientara: Yeah, I have a friend who has an MCI board and I was never big fan of them there, but they did have a certain character to them. And, you know, one thing that the 500 series is good for is you don’t have to buy the whole board. I can get the MCI, you know, the preamp, and then I can get an API preamp, and then I can get a purple..

RRFC: Purple preamps.

Zientara: Yeah, purple, anything. And you could mix them together and you could try them out and see which ones you like, see which ones you don’t like, and you know, if you don’t like it, just pull it out and sell it.

RRFC: Very true. And they’re fairly affordable, usually between two, maybe to eight hundred dollars or something for a really high-end API.

Zientara: Yeah. Yes, they are. I haven’t seen any for $200, but…

RRFC: Well, I just mean like on the eBay you might be able to find something.

Zientara: Yeah. Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah, absolutely. You know, talking about eBay, this is a great time for setting up a recording… it’s both a great time and it’s a terrible time for setting up a recording studio. Terrible because if you’re just trying to start out in a recording studio, you’ve got a lot of ground to make up and to cover with a lot of people because they’ve set up… you know, musicians and bands have set up home studios in their homes that are pretty elaborate. So you’ve got to go against, you know, a big rush of a lot of other people doing it. But a lot of the equipment is really cheap and you can get it really cheap. It’s just phenomenal. I just love… I mean I’ve gotten, you know, just Behringer mixers scattered all around my studio in the studio area for headphone amplifiers. An entire mixer for one pair of headphones because they’re cheap. And not only that, but they can mix it together. They can put effects on it. They can, you know, change the tones of things. So, that would never have happened, oh, you know, 30 years ago, 40 years ago.

RRFC: Right.

Zientara: Just would never see something like that. So it’s good. It’s a good era to live in. I mean I think it’s fun times in a lot of ways, but it’s also, you know, it’s very challenging too. Like I said. You know, recording is undergoing a lot of processes. You know, your magazine just going to totally online you know, was a move for certain reasons and those same reasons are permeating into the industry.

RRFC: Right. Yeah, a lot of overhead, you know, speaks to how much you can stretch yourself I suppose.

Zientara: Yeah. Yeah, absolutely. Absolutely.

On Making Today’s Apprentices Tomorrow’s Pros

RRFC: So, how do you love being a mentor now?

Zientara: I love it. I love it. Like I said, I’m passing on my bad habits. And, you know, it’s a type of thing where, you know, I just enjoy showing people what I know because I don’t see any purpose in hiding any of it. It’s just crazy. So, as a matter of fact, it’s almost criminal. I mean, you know, if you have certain knowledge and if you could pass on some secrets or tips or little things, if it’s compressing in such and such a way but you need to pass it, or do it in such a way, you know, how to do that. Or how to connect up this to that or… I was just talking on the phone with someone who has a certain interface and they’re wondering what kind of board to build and we’re going through all the different combinations of how it could be done. And this is one of my students. And what are the advantages and disadvantages of everything we’re looking at. I just love, love doing that. It’s great.

RRFC: Right.

Zientara: And you know, you’re going to meet the band by nature of a client and a service type of agreement rather than meeting them, you know, from a stage. So it’s totally different. And I don’t really know where the industry’s going, but I do know that the studios that are surviving have to offer the home studios something more. Either in equipment, but equipment then again is a monetary thing. In other words, if you have enough money you can buy, you know, some great, great equipment. And you could probably lure people and bands to come there. But at that point you’re opening up a studio.

RRFC: Right.

Zientara: And the other part of it is expertise and just the general vibe of the place. And if you have that, that’s a big, big part of things. One of the things I tell my students, and we talk about quite a bit, is just being a diplomat. And an ambassador and working through problems that bands inevitably have or musicians inevitably have or anybody who wants to record inevitably has. They could be recording a book on tape and there could be problems arising from what they’re doing. And just working through it and solving them for them. And they’ll remember that. And I think people’s memories of problem-solving experiences are gonna survive with the people. And they’ll remember that and they’ll pass it on and as you know, like, the word of mouth for a recording studio or anybody who wants to record, even someone who doesn’t have a studio, just a producer or an engineer, an outside, freelance engineer. If you have a good reputation, you’ve got it made.

RRFC: I don’t blame you. And so, when was it that you knew, like, ‘Oh, I’m gonna be doing this for the rest of my life.’

Zientara: I believe, quite frankly, that’s something that’s never dawned on me. At any moment, I expect to delve into painting and print making. The moment hasn’t come yet.

Notes:

50 years experience in the music industry and still going strong. Has worked with The Foo Fighters, Fugazi, White Zombie, Jimmy Eat World, Special K, Bad Brains, Minor Threat and many more.

Learn in Don Zientara's Studio in Arlington, Virginia.

-

Don Zientara

Recording Connection Audio Institute2701 S Oakland St Arlington, VA 22206, United States(571) 317-0065